"Dumb" Government Data

I recently was named a member of the Mayor’s Open Government Advisory Group. Among the things that the Group will be tasked with is “[e]stablish[ing] specific criteria for agency identification of additional datasets.”

Much has been written on the publication of high-value datasets, including some critiques. It is, in many respects, completely sensible to prioritize inherently useful data. But, in my experience, the focus on high-value datasets is a missed opportunity for governments to publish “dumb” data in machine-readable formats. In some situations, prioritizing dumb data may be the most important thing of all.

Dumb and Dumber. Photo from tom-margie at <https://secure.flickr.com/photos/tom-margie/2079121875

Defining “dumb” data

What do I mean by “dumb data”? I define “dumb data” as data that is descriptive of immediately perceptible things.

This definition encompasses two important features:

Perceptibility. First, dumb data must be completely, obviously, there. It should not require measurement or analysis to generate the data.

Descriptive. Second, dumb data must be descriptive–not normative or evaluative. If it requires a judgment call about how to calculate the data, it’s not a good candidate for dumb data.

For example, if I were to describe an individual, high-value data might include information about the individual’s hobbies, or educational attainment, or even zip code. By contrast, dumb data would include information about the individual’s height, hair color, and perhaps his or her name.

An individual’s height is immediately perceptible and utterly descriptive. An individual’s hobbies, by contrast, are not.

Take another example: sports. In sports, dumb data comes in the form of nightly box scores. When did the winning team score the winning run? Check the box score. Which team is hot going into the playoffs? Well, that’s not something included in dumb data. You might be able to discern that information from dumb data, but it is not itself dumb data.

Dumb data inaction & in action

Having defined dumb data, we turn to the utility of managing dumb data. In one sense, dumb-data collection might seem an enormous waste of time and effort. After all, if dumb data is immediately perceptible, why bother capturing, storing, and publishing it?

Here are three vignettes of where, in my experience, dumb data matters in government:

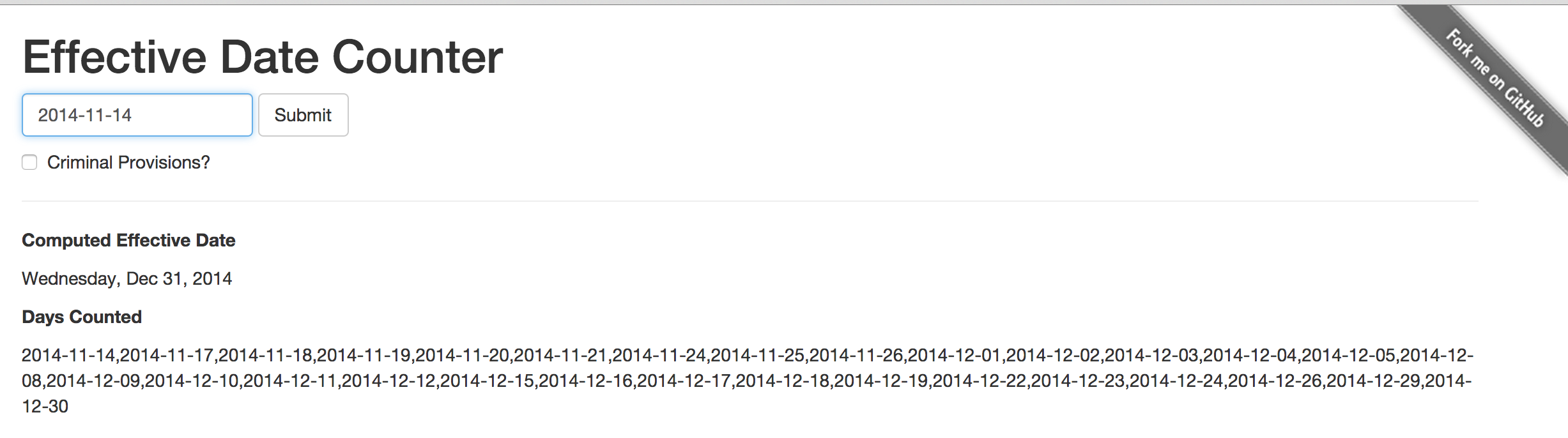

1. Effdate: An example of dumb data inaction

One of the very first applications I built is a little tool called Effdate. Effdate is a very simple application. It does only one thing: it computes the effective dates of District laws.

As the readme explains, until I built Effdate, “calculating the [effective date of a particular law] required reference to several calendars and hand counts.” This is so because, to calculate the effective date, one needed to know whether at least one chamber of Congress was in session on any given day.

It turns out, the calendar for a legislature is dumb data. What officially happens on any given day is entirely knowable and descriptive.

But, even though the Framers of the United States Constitution saw fit to require Congress to “keep a Journal of its Proceedings, and from time to time publish the same,”1 and you can browse the Congressional Record, there is no way to get an authoritative list of the days that Congress is in session.

Instead, I had to write a script that checks the Government Printing Office website to see whether either chamber has published a Congressional Record on any given day. The end result, dumb data for the House and dumb data for the Senate.

And lest you think that publishing the dumb data of calendars is a worthless effort, consider this post by Daniel Schuman.

2. Legislative committees: An example of dumb data inaction

At the D.C. Council–as in many legislatures around the country–there is an important biennial tradition: committee assignments. The United States Senate’s website observes that:

Committees are essential to the effective operation of legislative bodies. Committee membership enables members to develop specialized knowledge of the matters under their jurisdiction. As “little legislatures,” committees monitor on-going governmental operations, identify issues suitable for legislative review, gather and evaluate information; and recommend courses of action to their parent body

At the Council, committee assignments and committee jurisdictions change over time. In the next Council period, as a result of the election cycle, at least four Council committees will be under different leadership.2 In our Legislative Information Management System, or elsewhere on our Council website, however, we do not have a simple list of the committee chairs or of the committees’ responsibilities.

Committee assignments are dumb data. Once the committees are announced, everyone knows who’s on a committee. Even though it’s dumb data, I guarantee that when the Council reorganizes in Council Period 21, my office will be inundated with requests for a list of the committee assignments.

One smart way to use the dumb data will be to recognize that the same dumb data that we use to generate the Council rules and the Committee assignment list can also be used to populate the Council’s website (and the lists maintained by every one who cares about such things). It’s not hard to imagine that, once governments get in the habit of publishing this sort of dumb data, others inside and outside government would spend less energy trying to replicate it.

3. members.yml: An example of dumb data in action

As I mentioned at the outset of this post, I am a member of the Mayor’s new Open Government Advisory Group. On the Advisory Group’s website, I posted a number of documents, such as Agencies’ Transparency Reports and the Mayor’s Order establishing the Advisory Group.

But, I also decided to embrace dumb data and publish three dumb datasets: (1) a list of the Advisory Group’s members; (2) a list of the agencies’ transparency reports, and (3) a list of the meeting dates.

At this stage, it is far too early to tell whether any of these datasets will prove useful to anyone else. But, even if no one else finds use in them, they’ve already earned their keep. That’s because I actually used the data to build the website. I captured the data, made it machine-readable, and then used that data to populate the site’s pages. When changes are made, for example, to the membership of the Advisory Group, all that will need to happen is an update to the dumb data file. That same dataset can then update the distribution list, the subcommittee lists, roll call votes (if necessary), etc. No muss, no fuss.

Why dumb data may matter the most

Having explored three different variations of dumb data, it is worth reflecting on a social form of dumb data: the #selfie.

Regardless of whether or not a selfie is a modern phenomenon, a selfie is quintessentially dumb data. It’s descriptive and immediately perceptible.

However you feel about selfies, two things are beyond dispute: one, they’re simple and ubiquitous to take and, two, people love to publish them.

Stop for a moment and imagine a world in which government data were simple and ubiquitous and government employees loved to publish the data.

If a selfie is the dumb data of social-media, can the government adapt the lesson in the form of machine-readable dumb data to promote open government? I believe the answer is yes because focusing on dumb data actually elevates some of our most important open government data.

For example, the United States Department of Justice’s website publishes a JSON file with an impressive 968 datasets. This is great! But, incredibly, exactly none of those datasets are any of the following:

- A list of Attorneys Generals;

- An organization chart;

- The budget for the current fiscal year;

- Title 28 of the United States Code (the enabling legislation for the Attorney General)3

That’s not to say these records don’t exist. They do. But they’re not considered datasets. Incredibly, they’re too important for the JSON treatment.

The importance of dumb data has actually limited its publication. The reason why the days Congress is in session is not published in CSV? Too important! Why committee assignments are not published in YML? Too important! Instead, we have elaborate portals, webpages, white papers, reports, etc., to publish this information.

This is an opportunity lost.

By reimagining these records as dumb data, government employees may begin to appreciate that they’re not just building a website. They’re contributing knowledge that can be instantaneously shared and used in different fora.

To be more concrete for a moment, imagine you were asked to research whether any of the Attorneys General ever said anything publicly about the Third Amendment to the United States Constitution. Of course, you could search with “Attorney General” and “Third Amendment.” But, what if they later became a Supreme Court Justice? How could you capture that without using all of their names. In fact, how many Justices of the Supreme Court were Attorneys General? Without dumb data, answering these really basic questions is no trivial matter.

But if a government employee (or contractor) used a dumb dataset to power the biography page, this research would be feasible. And when the website is eventually updated, there wouldn’t be any need to screw around with HTML or Content Management Systems. You’d just add a new record to the dataset.

A modest proposal: Governments should publish dumb data

I hope by now that I have persuaded you that capturing and publishing dumb data would be a smart thing for governments to do. Happily, it is also an easy thing to do. Dumb data does not need to exist in a fancy web portal. Generating dumb data does not need to be done once a relational database is created. Dumb data does not require sophisticated instrumentation or fancy software.

Collecting and publishing dumb data can be as simple an act as putting something into an Excel spreadsheet and exporting it to CSV. Heck, if you do not want to do that, just save it as an Excel spreadsheet. Someone else can convert it for you.

If you are feeling adventurous, make a YAML file. I’ll even help you do it. Seriously.

My theory is that once government employees start thinking about our everyday, humdrum observations as “data,” the world can start to look a little different, a little more fun, and a lot more connected.

If 2013 was the year of the “selfie”, maybe 2015 can be the year of “dumb data.” Time will tell.

“U.S. Const., art. I, § 5, cl. 3” ↩︎

Councilmembers Muriel Bowser, David Catania, Jim Graham, and Tommy Wells chaired the Economic Development, Education, Human Services, and Judiciary and Public Safety committees, respectively. ↩︎

By contrast, title 21 of the United States Code, which concerns the Controlled Substances Act, is the second item on the list. ↩︎